Auckland, Sydney, Toronto & Vienna – 4 different cities, 3 common themes

| Writer |

|---|

| Marcus Ng |

Scattered across the globe, the four 2016 Special Mention cities may appear to have little in common. But details of their transformations reveal how common themes and priorities, translated into long-term plans that reflect local needs, have guided them to become more liveable and sustainable cities.

Cities mentioned in this article:

Auckland, Sydney, Toronto, Vienna

Auckland, Sydney, Toronto and Vienna – the foour Special Mention Cities of the Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize 2016 © Urban Redevelopment Authority Singapore

Auckland, Sydney, Toronto and Vienna – the foour Special Mention Cities of the Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize 2016 © Urban Redevelopment Authority Singapore

Four cities from three global regions – Oceania, North America and Europe – are named Special Mentions of the Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize 2016: Auckland, Sydney, Toronto and Vienna. These cities serve as cultural and commercial centres in very different parts of the world, but what they have in common is a commitment towards greater liveability that has made a real and enduring difference in the lives of their communities.

Each of these cities has in recent years embarked on an ambitious programme to address unique challenges as well as nurture a living environment that offers spaces for both people and nature. The solutions devised by each city have been tailored to the specific needs and nuances of local communities. But it is possible to identify three shared themes that underpin the transformation of these cities into exemplars of urban development: support for local communities and cultures; investments in the environment and public spaces; and a long-term plan that involves the city’s leadership, stakeholders and residents.

Culture and communities

He tangata, he tangata, he tangata (‘It is people, it is people, it is people’) is a Māori proverb that guides Auckland’s policy-making processes, which strives to put the people first, not least the first-peoples of New Zealand’s largest city. Though a cosmopolitan city of 1.5 million, Auckland cherishes a special relationship with its indigenous Māori; government decisions and programmes must take into account the concerns of an independent Māori statutory board.

Many of Auckland’s Māori and Pacific Islanders, who make up a quarter of the population, live in the city’s poorest areas in the south and east. To boost the liveability of these once-neglected neighbourhoods, the city is working closely with local residents through the Southern Initiative and Transforming Tamaki programmes, which provide targeted assistance such as trades training for youth and improved housing and healthcare facilities. In Glen Innes, another disadvantaged suburb in the east, young residents can now learn about, perform and celebrate their culture in the Te Oro Arts and Music Centre for Young People, an award-winning multi-purpose space which opened in 2015.

In Sydney, where the landmark Opera House defines the waterfront, culture forms an integral element in the city’s character and future. Sydney’s long-term strategic plan, Sustainable Sydney 2030, entails the making of a culturally alive city filled with theatres, libraries and cultural spaces. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, which were historically marginalised, have also been extensively consulted for the strategic plan; one result of this is the decade-spanning Eora Journey, which aims to improve these communities’ access to education and employment opportunities as well as provide platforms for cultural expression and mutual understanding between the city’s diverse residents.

A newcomers welcome info desk at a Toronto public library © Urban Redevelopment Authority Singapore

A newcomers welcome info desk at a Toronto public library © Urban Redevelopment Authority Singapore

Toronto, meanwhile, owes its cultural diversity to a history of immigration, with nearly half of the population being non-native Canadians from over 170 countries and speaking more than 160 languages. For newcomers, the experience has increasingly become one of welcome and facilitated spaces: local libraries offer helpdesks with multi-lingual, empathetic staff as well as facilities that make it easier to integrate and understand life in the capital of Canada’s Ontario province. The city is also investing strongly in its cultural fabric with support for both downtown cultural institutions as well as Local Arts Service Organisations that make creative and cultural activities more inclusive and accessible in under-served neighbourhoods.

Vienna, the city of Mozart and Freud, has no lack of cultural capital. But in remaking itself as a strategic hub between Eastern and Western Europe, Vienna has sought to preserve its historic centre but also move beyond the ‘museum city’ archetype with new facilities. Vienna’s Central Train Station, which opened in 2014 and replaced a former terminal station, is designed as a convenient through station with local and long-distance lines that have enhanced Vienna’s international connectivity, particularly with Eastern Europe. The station, which also houses a major shopping mall, has catalysed development in the surrounding Favoriten district.

The New Danube on the left and the Danube River on the right, with the 21km Danube Island in the middle © City of Vienna

The New Danube on the left and the Danube River on the right, with the 21km Danube Island in the middle © City of Vienna

Green and public spaces

Vienna also shines in environmental stewardship. Green spaces define Austria’s capital city, covering more than 50 percent of municipal lands, and ‘priority landscape areas’ are protected by a zoning plan that maintains a green belt for wildlife and natural habitats. Residents are also encouraged to plant vegetation in their yards and on their roofs.

Beyond Vienna’s cathedrals and museums, the woodlands that inspired Strauss’ waltzes and Mozart’s operas are also managed as integral elements of the city’s heritage. Spanning more than 105,000 hectares, these forests provide spaces for education, recreation and sustainable agricultural activities such as vineyards and pastureland. Their cultural and natural significance has been recognised by UNESCO, which designated the Vienna Woods as a unique Biosphere Reserve in 2005.

The Danube River that flows through Vienna is also being tamed through a long-term plan to alleviate floods and create new public spaces. By carving a channel called the New Danube, the city has created a flood protection measure that doubles as a water sports venue during non-flood periods. The soil excavated for the New Danube, meanwhile, was used to create Danube Island, a new public park right in the city centre.

Environmental sustainability also headlines Sydney’s vision to become a ‘Green, Global and Connected City’, which is being realised through programmes such as the Greening Sydney Plan for comprehensive urban greening initiatives and the Cycle Strategy and Action Plan 2007–2017. The latter aims to make cycling a first choice transport option, alongside walking and public transit, through a citywide cycleway network.

Sydney aims to increase its urban canopy cover © City of Sydney

Sydney aims to increase its urban canopy cover © City of Sydney

Meanwhile, the Greening Sydney Plan seeks to increase 50 percent of its urban canopy cover by 2030 by creating more tree-lined streets, acquiring land for parks and making greenery a requirement in new developments. Having more green spaces also contributes to better community relations and confidence, as seen in Redfern, a crime-ridden inner-city neighbourhood that turned around following an injection of public parks and playgrounds.

Over in Toronto, good urban design of common spaces is key towards attracting people and businesses back to the city centre. Downtown Toronto had suffered a decades-long hollowing out to suburban sprawl, but this trend is now reversing thanks to the creation of ‘complete communities’ and ‘complete streets’ that offers multiple transit options, walkability and a revitalised waterfront along scenic Lake Ontario.

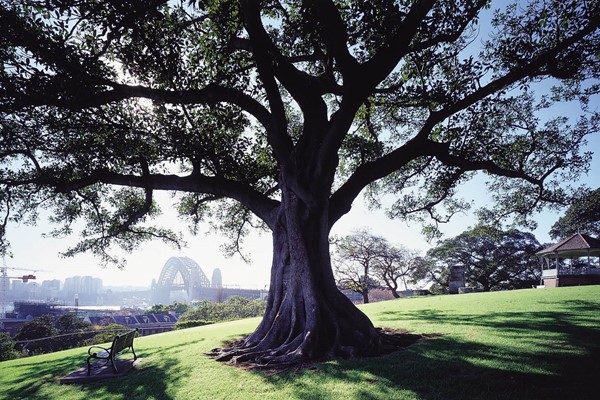

Auckland, too, has capitalised on its waterfront, by transforming its old wharves and harbour quarters into residential and commercial zones with attractive public spaces where people can dine, play and savour the maritime landscape. This vision also takes into consideration the traditional cultural significance of Auckland’s seafront, through support for Māori art and festivals, and strives to be a ‘blue-green waterfront’ that enhances the marine ecosystems upon which many Aucklanders depend for their livelihood.

The revitalised Wynyard Quarter along Auckland’s waterfront © Jonny Davis

The revitalised Wynyard Quarter along Auckland’s waterfront © Jonny Davis

Long-term planning and leadership

Auckland’s concerted efforts to rejuvenate its waterfront and engage local communities were possible only as a result of a bold reshuffle in 2010 that merged seven city authorities and a regional authority into a ‘Super Council’ led by then-Mayor Len Brown. This in turn made possible a long-term Auckland Plan to create ‘the most liveable city in the world’ by 20401. Just three years has passed since its launch in 2012, but the Auckland Plan is a step in the right direction that shows how a city in a remote part of the world can develop in a sustainable and socially integrated manner.

Sydney, too, is thinking decades ahead with its Sustainable Sydney 2030 vision, which enjoys the strong support of the Lord Mayor Clover Moore and City Council, who have aligned their planning priorities with feedback from the ground. The vision has also paved the way for the most extensive community engagement exercise with stakeholders and residents in Sydney’s planning history, an 18-month process that fostered understanding and cooperation between the government, private sector, civic groups and urban communities.

Over in Toronto, the goal of rejuvenating the city core stems from a long-term Central Area Plan that has been sustained by the city’s leadership despite limited funding from the Federal and Provincial Governments. The city still faces a shortage of affordable housing and transit budget cutbacks, but has persisted in investments in public spaces and social integration that will yield visible returns over time.

Finally, Vienna’s future to 2025 and beyond is being charted by a STEP 2025 Urban Development Plan with 13 Key Areas identified for focused developments across the entire city. Already recognised as one of the world’s most liveable cities, Vienna has prevailed under the long-term leadership of then-Mayor Dr Michael Häupl, and along with the other Special Mention cities of 2016, is seeking to build a sustainable future through environmental leadership and common spaces that enhance the quality of life for its diverse communities. O