A Prize to inspire – Celebrating cities that achieved lasting change

| Writer |

|---|

| Marcus Ng |

What are the qualities that define liveable, vibrant and sustainable urban communities? Why should cities embrace participatory planning and include their wider regions in their long-term vision? We speak to Flemming Borreskov and Prof Wulf Daseking on the trends and thinking shaping the Prize and cities worldwide.

Cities mentioned in this article:

Medellín, Copenhagen, Malmö, Freiburg im Breisgau

Medellín – once among the most violent cities in the world – is today a transformed city that celebrates life and known for its urban innovation © ACI Medellín

Medellín – once among the most violent cities in the world – is today a transformed city that celebrates life and known for its urban innovation © ACI Medellín

“The message – that participatory planning can usher in real change – should give hope to all those not living on the ‘sunny side’ of society,” declares Wulf Daseking. “Greater integration – not separation – of all parts of the population should be the way forward for cities.”

Daseking, who is Professor of City Sociology at the University of Freiburg in Germany, was speaking with Medellín in mind. In his view, this Colombian city and the 2016 Laureate of the Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize achieved effective and lasting change as a result of the city’s decision to integrate their population, especially those living in the poorest barrios or neighbourhoods, early in its transformation process. This approach led to innovative urban solutions such as the MetroCable cable car system, which not only allows residents of distant barrios to easily commute to other parts of the city, but also double as vibrant public nodes for sports, leisure and education.

Flemming Borreskov, President of the Catalytic Society in Denmark, shares this view, that Medellín owes its success to leaders who have “the ability to listen” to the people in order to create solutions that address the challenges the city was facing. Another aspect that particularly impressed him was the continuity in the city’s governance. He says, “We saw both the present and the past Mayors receiving the Prize together, and even though they represent different political views, they respect each other and that is very important when you are planning and building a city, which takes years.”

Participation matters, and goes hand in hand with strong leadership and good governance, according to Borreskov. “I think many people focus too much on the strategic or long-term plan,” he remarks. “They tend to forget that to create cities for people – liveable, sustainable and vibrant cities – it takes leadership and good governance.” Borreskov regards cities as highly complex entities that he likens to living beings rather than physical or mechanical structures. “It is biology and people that we are talking about,” he says, “so it is important to have leadership that is nimble, adaptive, able to listen – but yet strong.”

On his part, Daseking observes that city leaders and planners are learning that it is in fact “much easier to bring projects forward when citizens are included in the discussion from the first step.” A culture of participatory planning, he says, can mean that “project delivery becomes smoother and faster, and the exchange of ideas drive up quality too.”

“I think many people focus too much on the strategic or long-term plan, [and] tend to forget that to create cities for people – liveable, sustainable and vibrant cities – it takes leadership and good governance.”

President, Catalytic Society

Reaching out to the wider metropolitan region

For the 2018 Prize, a new judging criterion is how cities include their wider metropolitan region as part of their long-term planning. Borreskov sees this as “a very natural development of the Prize” that expands its perspective “to a broader conception of the city: from just the city to the entire metropolitan area.”

“You have to look at the wider metropolitan area, which is characterised by the fact that there are strong ties between the legal entity that is the city proper and the wider region around the city,” he notes. These ties include economic and business links, social and family connections as well as transportation networks, all of which affect people who are living outside the city and working in it, and vice versa.

Daseking points out that the new criterion reflects the continuing trend of a “strong pattern of migration towards cities and metropolitan areas worldwide”, which had led to “terrible sprawls” around many megacities. Daseking observes that “in past times, planners were concerned almost exclusively with cities.” Now, he sees an urgent need for cities to be well-integrated with their surrounding region and to have coherent social, economic and environmental strategies that can traverse geographical distances as well as political differences.

The bridge that links two cities – Copenhagen and Malmö – in the Øresund Region © City of Copenhagen

The bridge that links two cities – Copenhagen and Malmö – in the Øresund Region © City of Copenhagen

This integration of city and regional planning is not an easy process, Daseking adds. One notable case, however, comes from the Øresund Region in north Europe that includes Copenhagen in Denmark and Malmö in Sweden (joint Special Mention in 2012). “This is an excellent example of collaboration across national frontiers, where different urban and national authorities have found a way to work together, especially in the sectors of public transport and housing,” remarks Daseking.

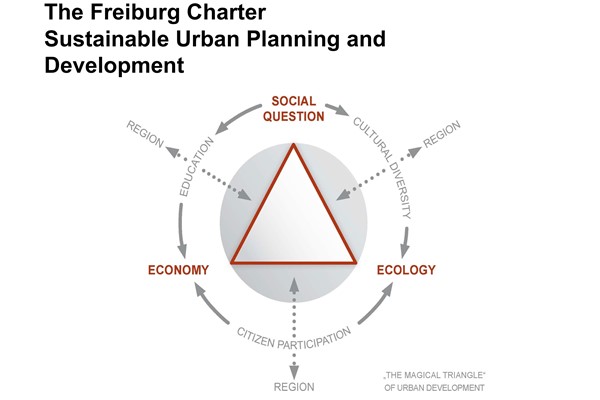

Another success story is the ‘Green City’ of Freiburg im Breisgau in south Germany, which lies close to both the French and Swiss borders. In 2010, a team led by Daseking (then the city’s Chief Planning Officer) drafted the Freiburg Charter, which guides the city’s sustainable urban development and planning process, and regards cities and their regions as “inextricably interwoven and interdependent.” As Daseking explains, “City and region – even across country borders – must be regarded as a closely bound organism; they simply have to find a way to cooperate together.” This approach has led to collaborations with nearby municipalities in Basel (Switzerland) and Mulhouse (France), with all three cities sharing an international airport based near Mulhouse.

Consideration for the wider region forms an integral part of the Freiburg Charter for Sustainable Urban Planning and Development, according to Professor Wulf Daseking © Wulf Daseking

Consideration for the wider region forms an integral part of the Freiburg Charter for Sustainable Urban Planning and Development, according to Professor Wulf Daseking © Wulf Daseking

Celebrating excellence in city planning

Good leadership, a long-term outlook, participatory planning – these are qualities that will help cities create a sustainable and high quality living environment for their residents. In the case of Medellín, Daseking personally sees a city that embodies such qualities and has “harnessed the raw ingredients of creativity, sensitivity, power and courage” to show that “it is possible to create a future with a better quality of life for all.” He adds, “These qualities provide the basis for the successful functioning of cities, and this was the message that I hope to send to other cities across the world.”

Daseking expresses his hope that the Prize will continue to celebrate excellence in city planning from all continents and also recognise the struggles and successes of cities that are fighting to improve the living environment for their residents and wider regions. “The Prize should encourage and give hope” he says, adding that the Nominating Committee has always striven to “judge all entries fairly and consistently.”

“Every city is a unique entity,” maintains Borreskov. “You cannot copy and paste solutions from one city to another.” What he hopes instead is for cities all over the world and their leaders to be inspired by the creative urban solutions devised by the Prize Laureates and Special Mentions. “This is the main value of the Prize,” he says, “not just to the city that receives the Prize but the inspiration it gives to thousands and thousands of other cities around the world.” O