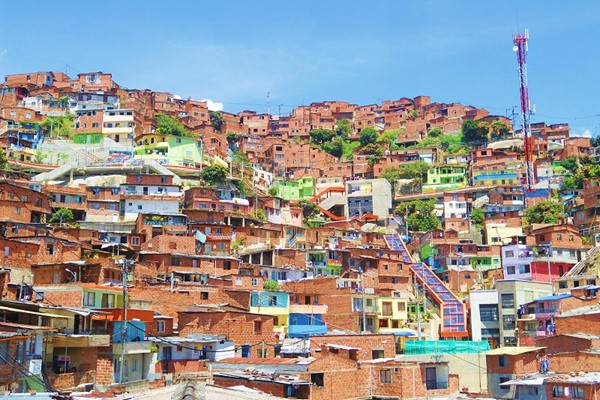

Medellín – Transforming barrios, transforming Medellín

| Author |

|---|

| Tan Chui Hua |

Like many developing cities, Medellín experienced a rapid surge in population from the 1950s. The proliferation of informal settlements brought along a host of issues from violence and inaccessibility to housing safety and lack of public infrastructure. What made Medellín stand out, however, was its bold, grounds-up approach to tackling informal settlements and their associated issues. Following two decades of sustained effort, Medellín today demonstrates the remarkable urban transformation that can be brought about with determination, vision and creativity, even in the face of limited resources.

A network of escalators in Comuna 13 San Javier helped improved vertical mobility in the neighbourhood © Carlos Escobar

A network of escalators in Comuna 13 San Javier helped improved vertical mobility in the neighbourhood © Carlos Escobar

The story of Medellín’s population surge is one echoed across many developing cities in Latin America, Asia and Africa. Rapid urbanisation since the 1950s saw an increase in opportunities for work and education in the city, turning Medellín into a migration magnet. In 1940, Medellín’s population hovered around 170,000. By the end of the 1990s, it had burgeoned to almost 2 million1.

Widespread informal housing quickly followed the mass migration, leading to a proliferation in informal high-density barrios (neighbourhoods). Many of these barrios spread upwards to the mountains encircling the city, which is located in a valley. Aníbal Gaviria Correa, who was mayor of Medellín from 2012 to 2015, describes, “We are a city of mountains, and many of our citizens live in informal settlements in parts of the mountains. This is a problem because sometimes we have landslides and people are killed.”

The list of challenges and hazards accompanying these settlements ran long – difficulties in establishing governance, violence resulting from drug gangs controlling different barrios, building safety, poverty, accessibility, lack of infrastructure, legal land tenure, and environmental degradation – to name a few.

These challenges are not unique to Medellín. What sets this Latin American city apart is its creative approach to integrating and resolving informal settlements, and at the same time, raising the quality of life for its residents.

Bold ideas to tackle informal settlements

In the early 1990s, Medellín began exploring solutions to integrate its informal settlements. Strapped by inaccessibility to funds, manpower and other resources, the city remained undeterred despite the considerable challenges for such an extensive undertaking.

The Circumvent Garden © Municipality of Medellín

The Circumvent Garden © Municipality of Medellín

“Informal settlements need new ideas,” recalls Jorge Alberto Pérez Jaramillo, Medellín’s Director of Planning from 2012 to 2015. “It is not possible to solve informalities with formal procedures, so we found new ways to intervene with a re-urbanisation methodology.”

Taking a bold step forward, the government embarked on an unusual move to gradually legalise informal settlements. Houses in the settlements were assessed, and those found to be structurally sound were legalised, while improvements to residences were also carried out. The move not only eased the burden of costly relocation programmes, it also recognised the residents as valued residents of the city and granted them dignity.

Improving housing quality and giving legal status to informal settlements marked just the beginning of Medellín’s transformation. Integrating the residents, who were often poor migrants from rural parts of Colombia, and at the same time raising their quality of life, was the larger objective.

Over time, social and infrastructural projects were launched in succession. The inaccessibility of informal settlements, especially those sited in the mountains, was a major concern. Using a blend of cable cars and escalators to connect to the metro system, the country’s first such system, new public transport networks were created. This was a critical move forward, as connecting those settlements to the city’s core opened up opportunities in work and education for residents.

Projects were planned and carried out to address specific needs and risks in each informal settlement. Raising the quality of life and self-sufficiency of residents was a priority, and that shaped initiatives such as the launch of new communal facilities and skills training programmes.

Parque Biblioteca España, or the Spain Library Park, established in 2007, demonstrates how public facilities serve as important spaces for residents seeking refuge from gang violence and crime. Located in a park near a metro station, the library is frequented not just by residents in the vicinity, but also those living much further away.

Parque Biblioteca España © Pepe Navarro

Parque Biblioteca España © Pepe Navarro

At the same time, the city’s sprawl of informal settlements continued to edge up the surrounding mountains. To check the growth, the city created an encircling green belt, called the Circumvent Garden, in 2012. The garden performs several critical functions – it reduces soil erosion, serves as the city’s green lungs, hosts community facilities and even farms. “When you destroy the forests for informal settlements, you also destroy Medellín’s environment,” said Gaviria. “The garden limits the growth of the settlements and gives more public space for people in the city and the hilltop communities.”

Making community ownership a priority

These projects, however, would not have seen such impact and success if not for the most critical element – Medellín’s culture of co-operation and community ownership.

When the city began its journey to reinvent itself in the 1990s, it was already infamous as the world’s homicide capital. “In the worst moments of our society, when we had become an unliveable city, we started to work collectively to build solutions,” Pérez explains. “Medellín has been able to develop a kind of social planning process with strong participatory involvement from the communities, and leadership from many stakeholders from the public, private, academic and social sectors.”

This collective spirit was crucial to the transformation of Medellín’s informal settlements. By bringing in key stakeholders, tapping on different pools of skills and creating opportunities for residents to take charge, the city managed to carry out effective projects despite limited resources.

Local and national authorities actively sought out researchers in the universities to collaborate with residents in identifying risks and needs of their settlements and drawing up plans and solutions. “We use universities as laboratories for the city – the social sciences, engineering, architecture and law schools are involved in creating solutions and transforming academic knowledge to public knowledge, and bringing that knowledge to the city and for the people,” says Pérez. “And we go into the barrios and work together with the communities.”

Drawn by the ground-up approach, local organisations such as non-governmental organisations, charities, the church and educational institutes became involved in different projects to improve the settlements. From determining the specific needs to creating opportunities for residents’ involvement, the city took care to enable community ownership. For instance, residents were employed by the city as guides on escalators built in their neighbourhoods. Through such efforts, the city saw to it that the programmes were relevant and sustainable in the long run.

Even more remarkably, this co-operative spirit saw to Medellín’s commitment to its transformation over two decades. Despite several changes in local government, the city continued on its path to better its environment and the lives of its vulnerable communities.

Improved public spaces, pocket parks and wall mural artwork in Comuna 13 San Javier © Carlos Escobar

Improved public spaces, pocket parks and wall mural artwork in Comuna 13 San Javier © Carlos Escobar

Forging ahead

Tackling its informal settlements from multiple angles was central to Medellín’s transformation. By integrating new migrants into its larger community, improving their environment, and building community ownership, Medellín has reduced its crime rates drastically while raising the quality of life for its residents.

It was not all smooth sailing. There were multiple challenges, such as having to negotiate with armed gangs who controlled certain settlements, a steep learning curve for the stakeholders, local resistance to community participation and community disagreement over plans for improvement. Two decades on, however, Medellín’s makeover was proof of its determination to forge on, regardless of limited resources and serious obstacles.

The benefits to residents were palpable. Surveys carried out after improvement works often revealed that the majority of residents felt that their quality of life had improved significantly. In many of the informal settlements, community ownership increased over time, and residents took it upon themselves to protect and maintain their public amenities and facilities. With improvements in building safety and establishment of the Circumvent Garden, the threat of landslides and their impact were also reduced.

Santiago Gómez, Secretary of Government of Medellín, is enthusiastic about the city’s continuing transformation. He says, “There are many programmes initiated by the past administration that are important, such as the land use plan. Continuity of such programmes, and continuing with more efforts to improve our city will be critical factors for Medellín’s success. Right now, we are making plans for the next four years. We want to further improve mobility and transport, build cycling routes, enhance security and ensure greater equality in our society. Most importantly, we need to continue to build Medellín’s culture – one where every resident loves the city and will work to make it better. We have developed and come very far from a difficult past, and we still have many problems and challenges. But we are willing to continue to fight for our city, and this, I believe, can inspire other cities in similar situations to do the same.” O

| Notes | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Imparato, Ivo, and Jeff Ruster. 2003. Slum Upgrading and Participation: Lessons from Latin America. Washington: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank |